World War II Airplane Turret Restoration

How war machines become war history.

The shed in Fred Bieser’s back yard looks deceptively ordinary from the outside. Corrugated metal walls are interrupted on one side by a pair of garage doors. It’s a big shed, the kind you have plenty of space for when you live outside Atlanta, GA. Most people would have to work to fill it with a lifetime’s worth of accrued junk, our spare furniture and boxes of books. Bieser, though, has filled it to the brim with thousands of parts from World War II aircraft.

Dozens of hand controllers and motors, used to turn the turrets that were once attached to bombers like the Boeing B-24, line narrow shelves. Seventy-year-old electronic components are strewn about, their insides exposed and corroded, awaiting repair. Three mangled turret husks–a few hundred pounds of crumpled and rusty metal–are pushed into one corner. That’s what most World War II-era turrets look like, these days, after decades in junkyards or scrap heaps.

Most turrets–but not all. In the middle of the shed, seemingly untouched by time, are two fully operational World War II aircraft turrets. They look almost brand new because Bieser put as much as 1000 hours of work into restoring each one.

A lifelong aviation fan, Bieser has been collecting turret parts, as well as other airplane relics and memorabilia, for more than 30 years. In the 80s, that meant going to salvage yards and aviation scrapyards, paying 50 cents a pound for mangled turrets that weighed hundreds of pounds. Taking apart that salvage was how Bieser first began learning the intricacies of turret restoration.

“They were usually in such poor condition there was no way I could damage them any more,” he says. “By disassembling these things I could learn how they were put together, and this really helped me a lot later on when I started putting them back together. So for about the first 10 years I just bought these things wherever I could find them. eBay came along at that point, and I started finding parts on eBay. Eventually I just built up an inventory of turret parts that I had squirreled away over the years.”

Restoring a turret to working order, much less getting it close to the state it was in 70 years ago, is even more difficult than it sounds. Surviving parts are in limited supply. And making new ones, Bieser discovered, isn’t really an option.

“Originally I thought I was just going to be able to take something to a machine shop and have it made, but as it turns out the technology 75 years ago was actually very highly advanced, and some of the stuff you can’t even make today,” he says. “A lot of it was top secret, especially the guidance systems, the gun computing sights…The Japanese and the Germans didn’t have it. Probably the most influential thing was the casting of molten aluminum, or in some cases magnesium. Magnesium’s pretty unstable material and they really pushed the envelope when it came to forming these parts and casting them…If you can find anybody that is willing to try it, usually the parts you get back are nowhere near as good as the parts that were originally made in the factory.”

With the enormous aircraft factories of the 1940s long gone, using surviving parts is the only viable way to restore a turret. After building up his inventory, Bieser began learning how to put the pieces together. He’s now fully restored nine turrets, each taking 1-2 years of on-and-off work. By now he’s worked out a process, which begins where you might expect: with the base.

Fixer-Uppers

Working on a turret requires getting at it from all angles, so Bieser had a welder fabricate a rolling metal stand that he could mount a turret to. The mounting ring which attaches to the stand was originally used to attach the turret to the airplane fuselage, and it connects to the platter, which supports the turret. 21 bearings allow the platter to roll on the mounting ring. Once the turret is attached, it can rotate 360 degrees on the metal stand.

Next, Bieser dives into the electrical system. “Most of the turrets I restore are electrically driven, and you want to start with two drive motors,” Bieser says. “One’s for elevation and one’s for azimuth. These drive motors, you have to restore them and make them work, and I’ve got a little test jig that I put them on where I can test the motor by itself. Once I’ve got the motors mounted to the actual base unit, I usually start with the electrical system. The hand controllers, and the junction boxes, [which] are full of relays. Occasionally I’ll find a vacuum tube, but most of the time it’s just relays and really large circuit breakers. Once I get the electrical system working separate from the turret, then I go ahead and restore the rest of the turret, which means putting in the rest of the bearings and cleaning and painting all the parts that go on it.”

Simple as that–turret restored! Almost. Hundreds of hours of work go into restoring “the rest of the turret,” which involves installing dozens of components in the correct order and hooking everything together.

The motors are a good example. On lucky occasions, Bieser lucks out and finds a working drive motor on eBay, though he still needs to get it serviced before putting it to work for the first time in 70 years. Usually, the motors he pulls off mangled turret husks are too damaged to repair. But sometimes they’re fixable.

“A lot of times when you find them they look like hell on the outside, but once you pull the cover off and clean the thing out and inspect it on the inside, the inside is really nice,” he says. “The drive motors are literally at the center of the turret, and if it’s crushed from the outside in, they kind of get protected, as long as they haven’t been laying underwater for 50 years.”

Another vital step in cobbling together turret components is testing them for fit. Because most World War II turrets are now crumpled, rusty metal, they yield a limited number of salvageable parts. Eventually, Bieser collects enough parts to Frankenstein one turret together, starting with the best base he can find to build off of. “Some of the turrets I [rebuilt] are literally six, eight, 10 turrets in one,” Bieser says.

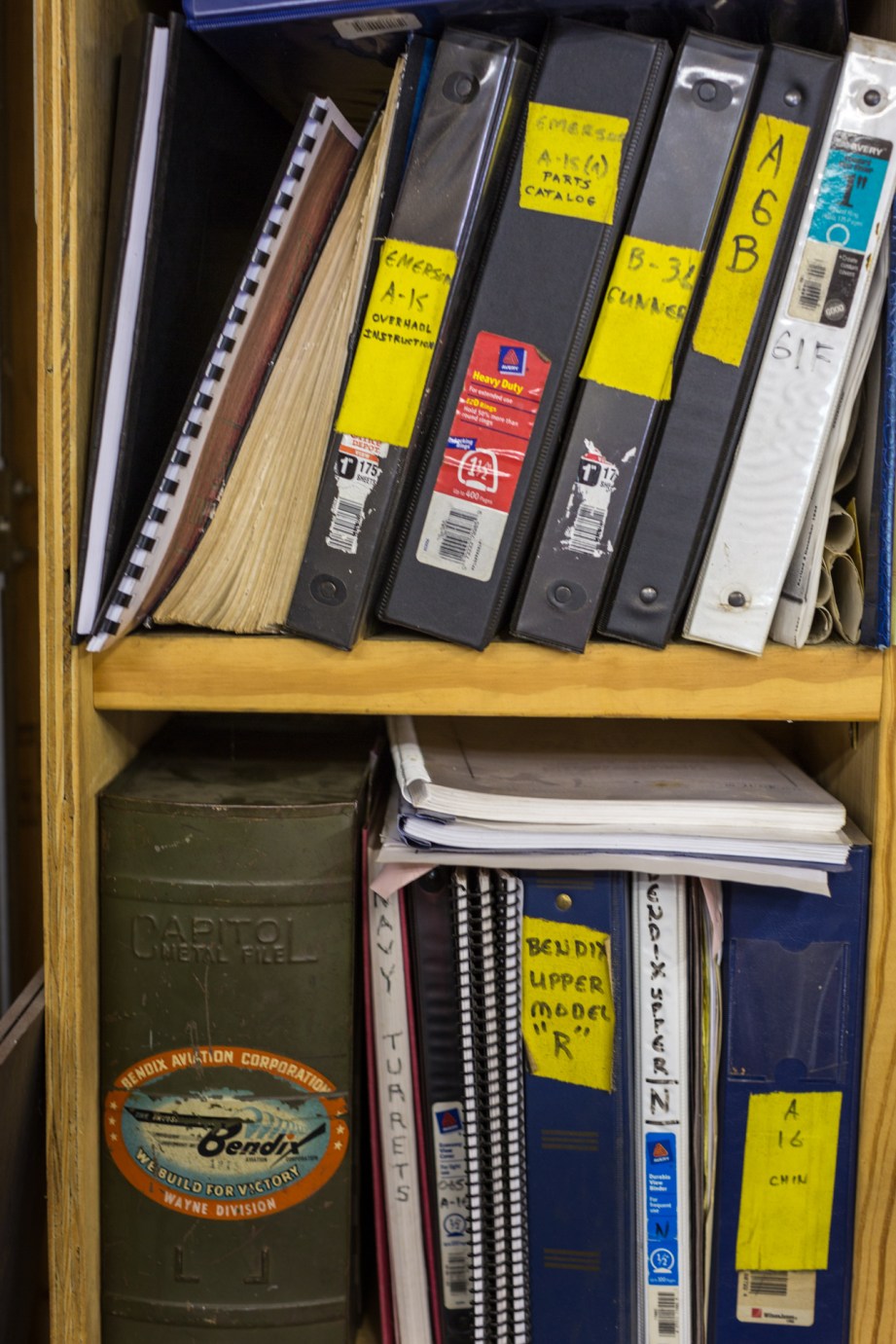

Combining parts from different turrets is tricky, because even the same turret models sport some differentiation. Over the years Bieser has built up an expansive archive of 70-year-old manuals from the military or the actual turret manufacturers, which often contain exploded diagrams of parts fitting together and electrical schematics. As vital as they are, the manuals vary in quality from manufacturer to manufacturer. Worse, they’re not always accurate.

“During the course of the war, every week or month the designers would change something according to how the war was going,” Bieser says. “So they were constantly being modified and updated. Part of the puzzle is trying to identify which part of the production run this particular turret was made in. There’s a lot of little clues that you can pick on that tell you what part of the production line this came from.”

Sometimes parts from different periods of a production run are compatible. Sometimes they’re not. Bieser compares them to 3D jigsaw puzzles.

“If you remember in Star Trek, they had a chess game that was on three different levels,” he says. “It’s kind of like the same thing for me. These things are really elaborately conceived and designed and fabricated and they have to go together a certain way, so there’s a lot of puzzle solving that goes into it… The most important part is testing for fit as you go. If you’ve got two parts, you want to check and make sure they fit together, and the next part has to fit behind it, and the next one after that. So there’s a procedure you have to go through that you’re constantly checking the fit, and the operation of these things as you go, especially for anything that has a bearing drive involved in it. You have to make sure there’s no binding, nothing sticking or any kind of a slippage.”

Over the years, Bieser has developed enough familiarity with the component manufacturers to find bearings and electric relays–parts that are almost always shot and need to be replaced–on eBay, even when they’re aren’t listed as aviation components. But some it can still take years to find all the parts he needs. And until he’s sure he own all the components, he doesn’t start building. Bieser has had some turrets in storage for 15 years, waiting for the right parts to take on a restoration project.

After rebuilding a particular turret model for the first time, subsequent restorations go quicker. Still, those take hundreds of hours of work for Bieser, and hundreds more for friends who help him out. Even when a turret is restored, the work’s not done. Showing them off is an entirely different challenge.

Safe for Kids

Bieser first started collecting turret parts and restoring turrets for a practical reason: They’re small. He worked on a Piper Cub plane as a kid, but knew he couldn’t afford a hangar big enough to house an airplane. So he turned to turrets, which are small enough to fit in a basement. But once he restored his first turrets and started to take them to airshows, he realized he’d found his niche. Turrets give Bieser an opportunity to teach future generations about World War II, and to honor the veterans who found in the war.

“Turrets are one of the most undertold stories of World War II, and it seemed to wrong to me that this part of our aviation history, particularly World War II history, was going untold,” he says. “Most people don’t even know what a turret is, and when they see one at an air show, especially the kids, when they see these things they’re fascinated by them, because they’re about as far away from a video game as you can get. And then when they see another little kid in there spinning around in it, they pretty much have to get in it. So there’s an educational potential right there, a teachable moment.”

The turrets don’t fire, of course; there’s no ammunition, and Bieser uses fake barrels that look and feel real, but are solid through the middle. Otherwise, they’re completely functional. Getting the turrets running at air shows and museums took some ingenuity for Bieser–and a whole lot of direct current.

Ideally, the turrets run off of 28 volts of DC power, so Bieser created a makeshift power supply by wiring pairs of 12 volt car batteries together. He’d charge up the batteries, take them to airshows, and use them to power the turrets for 20 to 30 minutes at a time, then scramble to switch to a new set when the turret sucked them dry.

“I was literally juggling car batteries trying to run these things, and that was just nuts,” he said. “Eventually I found power supplies that I could plug into the wall, and later on I found these power supplies I’m using now, which put out a true 100 amps of 28 volts DC.”

The turrets power on with the flick of a few switches, so easily that it’s hard to imagine how much work it took to provide them with a consistent power source. During World War II, the turrets were powered by Amplidynes, which offered dramatically more power than standard generators. The same technology powered early electric elevators, radar systems and naval guns.

Bieser doesn’t keep most of his turrets after restoring them; they’re sold to museums like the Mighty Eighth, which is working on completely restoring a B-17 Bomber. Restoration is his way of honoring the veterans who served in World War II, and he hopes that that teachable moment, the excitement kids have when they clamber inside one, will give future generations a tangible connection to history.

“Most of the planes you see at air shows do not have working turrets,” he said. “A very few of them in the last few years have started adding working turrets, but most do not. They just have a dome with a couple barrels sticking out of it. We hope to change that in the future, and I’m working with several aircraft owners now. So hopefully it will get better.”

5 thoughts on “World War II Airplane Turret Restoration”

Leave a Reply

One Day Builds

Adam Savage’s One Day Builds: Life-Size Velocirapt…

Adam embarks on one of his most ambitious builds yet: fulfil…

Show And Tell

Adam Savage’s King George Costume!

Adam recently completed a build of the royal St. Edwards cro…

All Eyes On Perserverance – This is Only a Test 58…

We get excited for the Perserverance rover Mars landing happening later today in this week's episode. Jeremy finally watches In and Of Itself, we get hyped for The Last of Us casting, and try to deciper the new Chevy Bolt announcements. Plus, Kishore gets a Pelaton and we wrack our brains around reverse engineering the source code to GTA …

One Day Builds

Mandalorian Blaster Prop Replica Kit Assembly!

Adam and Norm assemble a beautifully machined replica prop k…

House of MCU – This is Only a Test 586 – 2/11/21

The gang gets together to recap their favorite bits from this past weekend's Superb Owl, including the new camera tech used for the broadcast and the best chicken wing recipes. Kishore shares tips for streamlining your streaming services, and Will guests this week to dive into the mind-bending implications of the latest WandaVision episod…

One Day Builds

Adam Savage’s One Day Builds: Royal Crown of Engla…

One of the ways Adam has been getting through lockdown has b…

Making

Adam Savage Tests the AIR Active Filtration Helmet…

Adam unboxes and performs a quick test of this novel new hel…

Making

Weta Workshop’s 3D-Printed Giant Eyeballs!

When Adam visited Weta Workshop early last year, he stopped …

One Day Builds

Adam Savage’s One Day Builds: Wire Storage Solutio…

Adam tackles a shop shelf build that he's been putting off f…

Show And Tell

Mechanical Dragonfly Automata Kit Build and Review

Time for a model kit build! This steampunk-inspired mechanic…

I like the article format. I did a double-take, thinking I was on another site, but I do like it.

Was just about to say the same thing. Definitely a different take on how to present an online article. I like it.

Article was really interesting as well. I’ve always wondered why they don’t use turrets on modern aircraft but it makes sense that they would just be too fast.

I guess also air combat is fought over such vast distances with missiles and so on that an attacking aircraft is never going to get close enough to even see let alone shoot with conventional ammunition.

Thanks, this article was interesting! I love that there are people out there so dedicated to one seemingly small single thing. This kind of stuff wouldn’t exist otherwise.

Awesome! I’m a huge buff of ww2 aviation, amazing to see and hear the mechanical workings of these, and just imagine the cojones to lock yourself into a plastic bubble as 109s and fw-190’s come whizzing straight at you.

the B-52 actually does have a tail turret still, though now it’s remotely operated and was really a relic from being designed in the 1940s. It did shoot down a few mig-21s in Vietnam though!

Will mentioned ball turrets in a recent podcast, and then earlier today I stumbled across this poem about ball turrets (who knew people wrote ball turret poems!)

From my mother’s sleep I fell into the State,

And I hunched in its belly till my wet fur froze.

Six miles from earth, loosed from its dream of life,

I woke to black flak and the nightmare fighters.

When I died they washed me out of the turret with a hose.

apparently this poem is pretty famous – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Death_of_the_Ball_Turret_Gunner

and will was mentioning that he didn’t know if they were glass or plexi, we now know from many sources that they were plexi.